ZEROHEDGE | Published February 25, 2025

Our political class is aflame, and our lawyer-ocracy is up in arms over President Trump’s executive order limiting the scope of “birthright” (or “soil-based”) citizenship to children of permanent legal residents. Children born to tourists, students from other countries, and others here on a short-term basis, plus people here illegally, are no longer to be regarded as citizens of the United States merely because their mothers happened to be on American soil when they were born.

Is that constitutional? Does the U.S. Constitution demand that virtually everyone born on our soil (basically everyone except for the children of diplomats who, by convention, are under their home country’s laws) be considered a citizen by birth?

Most lawyers and law professors think that the answer is yes. But is it quite so clear? The 14th Amendment reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Most of the discussion of this question thus far has focused on the meaning of the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” and the prevailing view is that it was meant to include everyone who was, generally speaking, subject to American law. Although the Supreme Court has never ruled on the case of a child born to foreigners who are only here briefly, it has suggested that it would include them in the set of people who are citizens at birth.

Critics of this position hold that the amendment applies to cases in which the U.S. has complete jurisdiction over the person and note that there are ways that the scope of American jurisdiction over citizens and permanent residents is different than for people who are merely passing through – in being subject to the draft (and there had been a draft shortly before the amendment was ratified), to jury duty, and to many taxes (particularly since the people increased American jurisdiction by adding an income tax to the constitution in 1913), among other ways.

These discussions often turn to the debates in the Senate when they were drafting the amendment before sending it to the states so that the people, via their state legislatures, could decide if they wanted to add it to the Constitution. That’s a useful exercise, and it also would be helpful to see more discussion of what the people understood the amendment to mean when they had their state legislatures ratify it. Constitutional law is not legislation. The Constitution, including the amendments to it are the supreme law of the land because we, the people, made them so; so what we understood ourselves to be doing when we approved a text carries more weight than what senators understood themselves to be recommending to the people for approval. Our lawyers tend to think that’s too complicated. But it is not our job to make life easy for lawyers.

As a logical and grammatical matter, the full sentence “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside” only applies to people who already reside in a state. “And” in a sentence, per basic rules of grammar and logical construction, means both parts must be true for the full statement to be true. A person who does not reside in a state is not included among the set of people described by the language of the sentence. That is the strict reading of the text. If we are to take the sentence as one having a coherent meaning as a sentence in the English language, it implies that “the jurisdiction thereof” is limited to the kind of jurisdiction that only applies to people who “reside” in a state. Thus far, our discussion has barely considered this aspect of the text. (As I was finishing up the essay, I finally happened upon one article by Andrew Hyman, hot off the press in late January, that takes this into account, but that’s a rare exception.) Can that be a logical reading? It’s actually a fairly clear line. Tourists and others here on a temporary basis are not subject to U.S. jurisdiction in many ways. They don’t have several of the responsibilities of citizens – being subject to the draft, jury duty, paying income taxes, etc. Full-time residents who live and work here are a much closer call. The Civil War era draft included aliens who intended to become citizens. They are subject to more jurisdiction than tourists. And those here in violation of our laws are yet another category.

What is the implication of this? Can it be correct, given the lawyerly majority on the other side? Does it even make sense? Such a reading means that the text would not include people who resided in the Colorado territory before it became a state in 1876. The article Could they have meant that? Hyman finds that the issue was raised in debates over the text of the Amendment in Congress, and a change to include territories was rejected. It would not be unusual for judges, faced with the case of a person born in a federal territory, to decide that the text is imperfect and, therefore, to decide that those who reside in federal territory would also be included. (Implicitly, they would be adding “or territory” to the phrase “state wherein they reside.” Judges often do that sort of thing.) But when they do that, they are adding to the text, bringing what they take to be the spirit of the law, and using it to add to or modify the actual text. Adding those merely passing through the U.S. would be a much larger judicial edit to the text.

READ FULL ARTICLE

SOURCE: www.zerohedge.com

RELATED: Trump’s executive order on birthright citizenship draws more disapproval than approval

PEW RESEARCH | Published February 21, 2025

The day he returned to the White House in January, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that would redefine birthright citizenship. The order argues that children born in the United States are citizens only if they have at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident. Trump’s directive would mark a significant shift from how birthright citizenship has been applied for more than 150 years in the U.S., and it is currently being challenged in multiple federal courts.

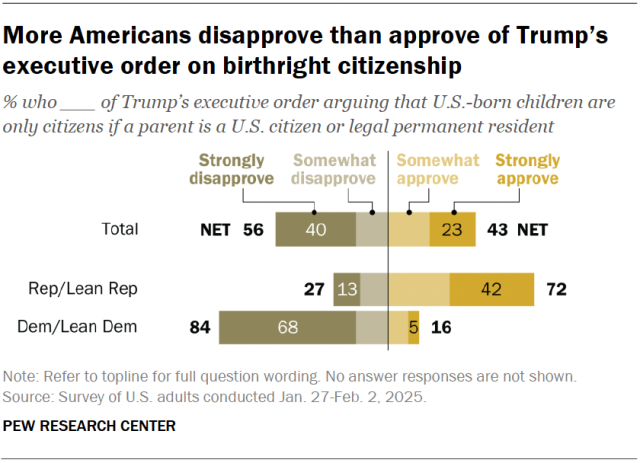

Overall, 56% of U.S. adults disapprove of Trump’s executive order on birthright citizenship, while 43% approve, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Disapproval is also stronger than approval: 40% of adults strongly disapprove, while 23% strongly approve.

Most Democrats disapprove of the order, while most Republicans approve of it. Yet Democratic disapproval is more widespread and more intense than Republican approval.

- 84% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents disapprove of the order, including 68% who strongly disapprove.

- 72% of Republicans and Republican leaners approve of the executive order, including 42% who strongly approve.

Views of executive order vary by race and ethnicity, age

Race and ethnicity

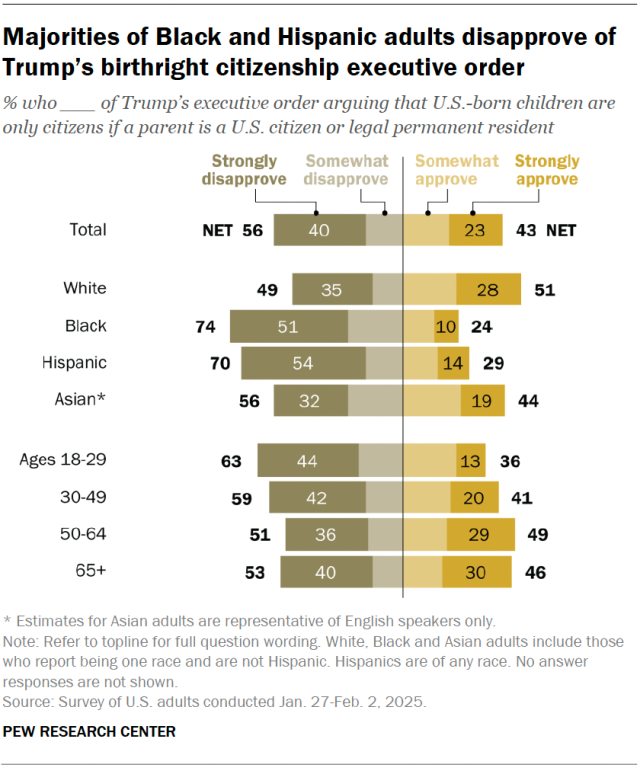

Black, Hispanic and Asian adults are more likely to disapprove than approve of Trump’s order on citizenship.

Disapproval is particularly widespread among Black (74%) and Hispanic (70%) adults. A narrower majority of Asian adults (56%) also disapprove. (Estimates for Asian adults are representative of English speakers only.)

White adults are split on the executive order: 51% approve and 49% disapprove.

Age

Adults under 30 are the least likely age group to approve of Trump’s executive order: Just 36% approve, while 63% disapprove. Those ages 30 to 49 are also less likely to approve than disapprove of the order (41% vs. 59%).

Views are about equally divided among adults ages 50 and older: 48% approve, 52% disapprove.

Among Republicans, approval of executive order differs by race and ethnicity, age

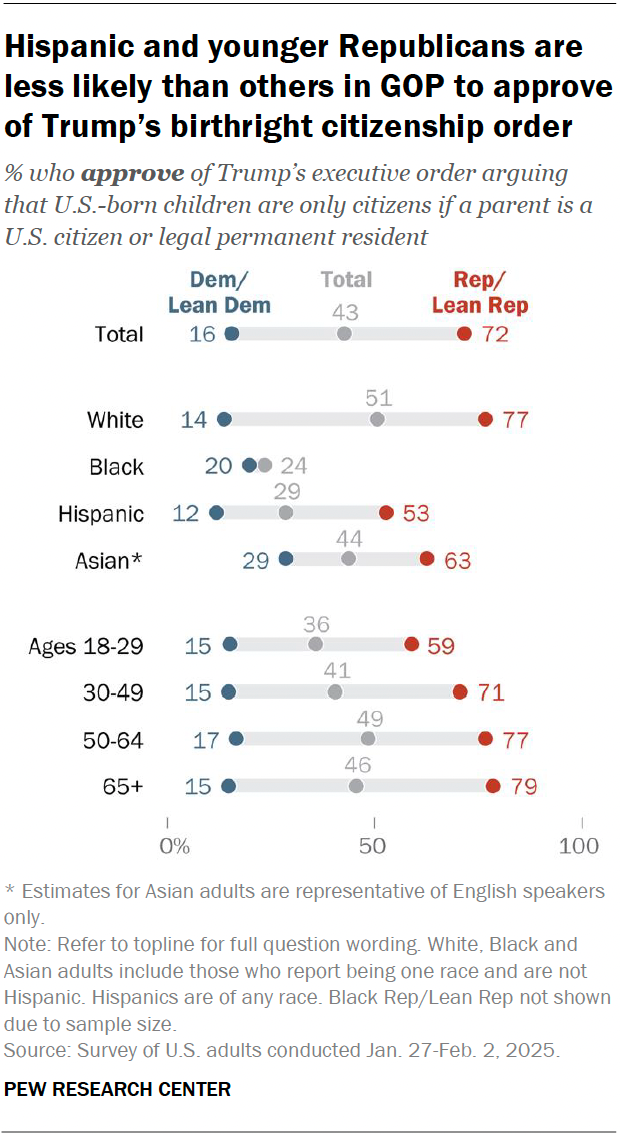

Across racial and ethnic and age groups, Republicans generally approve of Trump’s executive order on birthright citizenship, while Democrats across these groups do not.

Race and ethnicity

Among Republicans, there are differences in views by race and ethnicity. While 77% of White Republicans approve of the order, that drops to 63% among Asian Republicans and 53% among Hispanic Republicans. (Estimates are not available for Black Republicans due to sample size.)

Democrats overwhelmingly disapprove of Trump’s order regardless of race or ethnicity. Only about three-in-ten Asian Democrats (29%) and two-in-ten Black Democrats (20%) say they approve. Even smaller shares of White (14%) and Hispanic (12%) Democrats say the same.

Age

Majorities of Republicans across age groups approve of Trump’s order. But Republicans under 30 are less likely than older Republicans to do so: 59% approve, compared with 71% of those ages 30 to 49 and 78% of those 50 and older.

There are virtually no age differences in these views among Democrats.

Be the first to comment